By Peter Zaballos

The first car I bought out of college was a 1972 BMW 2002. I grew up in California, in the Bay Area. That part of the world was awash in amazing sports cars, and I was deeply obsessed with them. That 2002 in hindsight was a brilliant choice — it’s now a highly sought-after classic.

Years and years later, deep into my career as a full-grown adult, I learned to embrace the value of “lots of inexpensive failures” as the key to gaining insight and experience. Let’s just say that, to my “barely adult” me back then, the 2002 must just have been the embryonic moment when this belief took root.

I got the car shortly after taking a job at LSI Logic (see earlier posts on that company here, here, here, here, and here) and simply needed reliable transportation.

Where “reliable” is more properly defined as “fun, sporty, functional, and reliable.”

I grew up in a household where my dad saw cars as nothing but transportation and utility – he cared nothing about design or driving experience. In fact, when he bought our family station wagons, he told us his opening line with the car salesman was “show me the cheapest car you have on the lot.”

Not surprisingly, there was an awful lot of daylight between his view of the role a car could play in one’s life and my one.

But something I knew for certain was that the BMW 2002 was a glorious car. I saw them every day in and around Berkeley. The car is beautifully designed, with a near indestructible engine and transmission. It handles with precision and grace, and overall it’s one of the most lively, fun sports cars you will ever drive. It also served to clearly establish BMW as the sports car and sports sedan powerhouse it is today. The 2002 literally cracked open the US market for BMW.

And I’d been lusting after one of these for years.

I forget where I bought my 2002, but it was tan — how did I choose that color? — with a chocolate brown interior. An uninspired choice I would rectify much, much later in life.

Here’s a 1972 BMW in that awful color (not mine… mercifully I did not keep any photos of it)

Once it was in my hands, I immediately set to upgrading it. I had never worked on a car before, so this was a big, generally fun adventure.

My resources? Back then there was no internet. You had to go to the auto parts store and buy a printed manual for your car, like the Haynes Manual. The manual for my car covered six models, spanning 18 years. So let’s just say that for any particular model and year, the information was broad, but thin. The book, after all, was a little over two hundred pages. Maybe fifty pages for each model. Yep, broad but thin.

For the next two years I replaced or upgraded almost every moving part on that car. I worked on it during the weekends, since I had to drive it to work on Monday. This created a few somewhat stressful Sundays and some profound learning moments.

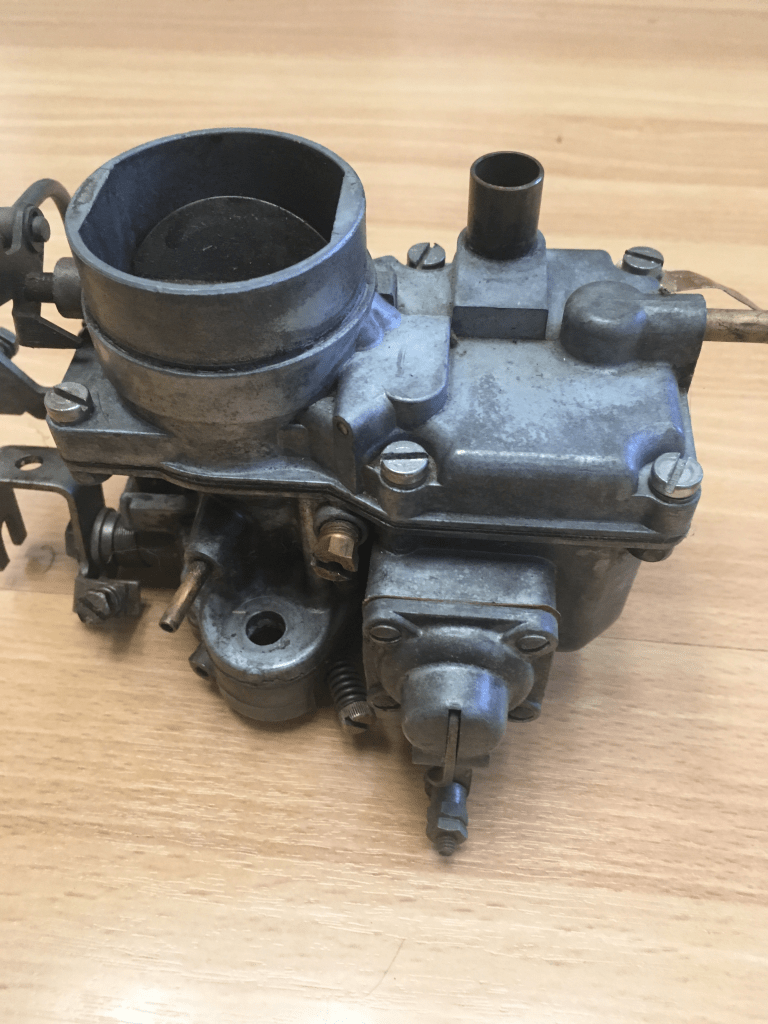

Like when I replaced the Solex carburetor that the factory provided with a higher performance Weber, marveling at the beauty of that device when I picked it up at the auto parts store.

Solex Carb Comparison with a Weber Carb (now including gaskets!)

I quickly took it home and got to work, removing the Solex, unplugging the vacuum hoses and throttle cable, scraping the intake manifold mounting area clean and then… realized I did not order a new gasket. Hadn’t thought about that. It was now after 4pm on Saturday. I borrowed my parents’ car and headed to the car parts store in a mild panic.

There I learned that car parts stores don’t stock gaskets for Weber carburetors — especially for obscure German cars — so I would have to order one, and it would be in by the next weekend. Oops. I kept my parents’ car that week. The following week, with gasket in hand, I mounted it and the Weber on the manifold and bolted it in place. But wait, there’s more.

Re-attaching the throttle cable was easy. But those vacuum hoses? I hadn’t labeled them when I took off the Solex. Oops.

This was decades before the internet, and the Haynes manual did not have diagrams for Weber carbs. The factory shipped them with Solexes, so that was the diagram in the book. And you can see that diagram was no help.

I did my best, but the engine ran a bit rough — I had clearly misconnected something.

Luckily there was a wrecking yard in the industrial flatlands of Berkeley that specialized in BMWs. I headed there, and the guy who ran the place, who was in his late 20s, opened the hood and within minutes “cleaned up the vacuum hose hygiene.” I remember that place was loaded with 2002s, Bavarias, and even a few 3.0 CSs. Today those cars — especially the 3.0 CS — are simply unobtanium. To think there was a wrecking yard containing just those cars is incredible.

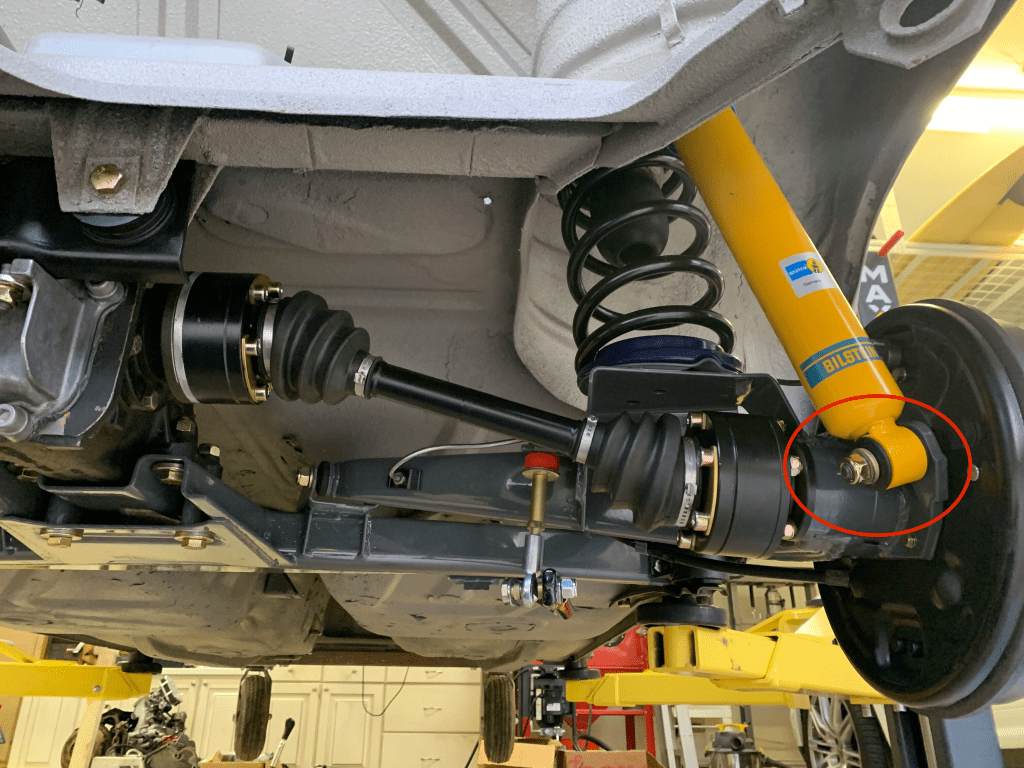

Later in my car upgrading journey I got new shock absorbers for the front and rear suspensions. I started with the front: I read the manual and realized I would need to get a spring compressor to replace the McPherson strut cartridges. I headed to the auto parts store and rented one for the weekend.

And of course the Haynes manual had diagrams for the front suspension but no real instructions for how to disassemble it and replace the shocks. I spent the better part of eight hours sorting all this out and successfully replaced the right front shock.

And with everything I learned from that right front unit, I was able to make quick work of the left one, replacing it in under an hour.

I did not have enough time that weekend to swap out the rear shocks, which were super easy. I could do that next Friday after work, before heading up that same night to Lake Tahoe to go skiing.

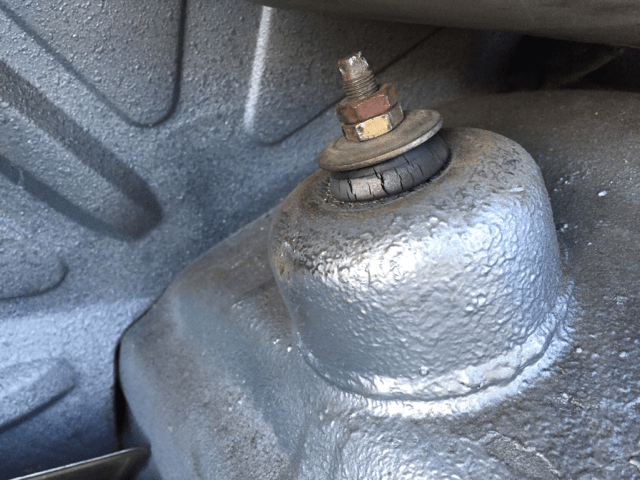

This work is pretty straightforward: after you jack up the rear of the car, it’s fairly easy to access where the shock is attached to the lower trailing arm of the rear suspension via a single bolt. The other end of the shock absorber is attached at the top of the top of the “shock tower” through the rear body sheet metal, also with a single bolt. That top bolt is accessed through the trunk, where it protrudes.

Super easy. I left work early to get home a little before 5pm, and by 6:30 I was on the road to Tahoe. It was dark by the time I left heading out on Highway 80 for the four-hour drive.

As I approached Auburn, I started to hear a knocking from the right rear of the car. I figured I could deal with that when I got to the condo I had rented for the winter. As I approached the mountains outside Auburn, it had started to snow lightly. By the time I was approaching Donner Pass, the snow was less than an inch and not sticking, so nothing to worry about.

But that knocking from the back was getting worse. So I pulled over, got a flashlight and looked into the right rear wheel well and could clearly see that the shock was banging around in the shock tower because I must not have tightened the second lock nut at the top of the shock tower, so both it and the securing nut had vibrated off. I opened the trunk and found the two errant nuts — at least now I could get everything put back together.

First I would need to jack up the right rear of the car, take off the wheel, get the shock back in place, and make sure I put everything else back together.

And as everyone who works on cars knows, the way you take a wheel off a car is to first loosen the lug nuts before jacking it up. It makes it so much easier to get the force you need on the lug wrench and eliminates the risk you’ll pull or push the car off the jack. And you reverse this when putting the wheel back on.

So I loosened all four lug nuts, got the car up on the jack, and went to work.

I was able to get the shock absorber positioned at the top of the shock tower and pushed the top through the mounting hole. My hands were getting pretty cold by then, though. You see I had plenty of skiing gloves, but nothing light enough to do this kind of car work, so I was working bare-handed. It was past 10pm and well below freezing.

I ran around to the back of the trunk, threaded the nut on the protruding shock absorber mounting bolt, and tightened it down, hard. By now my fingertips were getting numb.

I put the wheel back on the car as quickly as I could, threaded the lug nuts on and tightened them, lowered the car off the jack stand, threw all the tools in the trunk, closed it, hopped in the driver’s seat, closed the door as fast as I could, and cranked the engine over, pushing the heat lever to full on and the fan as well. My hands were frozen.

I got back into traffic, and pretty soon I was headed on my way, up and over Donner Pass.

Just after cresting the pass, headed downhill, I felt the right rear of the car drop with a loud CLUNK. I looked in the rear view mirror and saw a rooster tail of sparks arcing into the air behind me. And to my right I saw a wheel rolling past me, getting further away the more quickly I slowed down to stop.

Once the car stopped, I got out and ran around the back to see that the wheel I saw heading down the road was, in fact, my right rear wheel. Those sparks were the suspension scraping the pavement.

Holy crap, I forgot to tighten the lug nuts when I lowered the car off the jack. So I had sped off with loose lug nuts, and the nuts must have slowly worked their way off the lugs.

This was before cell phones existed. The thoughts going through my head then were pretty dire. 11pm on a Friday night, in the Sierras, light snow falling. In need of a tow. But then what? Where was I going to find a spare rim and tire for a 1972 BMW in Lake Tahoe?

Remember, this was the mid 80s, decades before BMWs became mainstream. As important, decades before tech bros took over Tahoe with their BMWs.

So I had no choice. I got out my flashlight to see if I could find… anything.

To the right of the car, the side facing away from traffic, I could just barely see a thin trail in the snow — the trail my tire had made as it fled my car. I followed the trail like a hunter tracking an elk, down the road and down the hillside.

Lo and behold, there it was, resting on its side. Easy to spot, with the light flickering off of those distinctive “bottle cap” wheels I had upgraded to.

I grabbed that puppy, triumphant, and hauled back up the hillside to my car.

But the lug nuts. There’s no way I was going to find those. Not only could they have come off one-by-one over a mile or two, they were the same color as the pavement. And while I had some spare parts with me, no one keeps spare lug nuts.

Then I did the math and realized I had twelve lug nuts on the three remaining wheels. If I took one off each wheel, I’d at least be driving with equally compromised wheel integrity.

So I backed one lug nut off each of the three remaining wheels, got the errant wheel attached with the three lug nuts I had just harvested, and was on the road again.

Ah, to be young and carefree.

I got to my rented condo well after midnight, and the weekend unfolded as planned. I spent two full days skiing with my crazy friends, and I mean crazy — we liked to jump off the cornice to the left of the Headwall chair at the resort that is now known as Palisades. More on that at a later date.

I drove home feeling somewhat triumphant, having averted disaster while having an awesome skiing weekend. Monday I went to the auto parts store and picked up four lug nuts. Why just four? That’s all I needed, obviously. I would never do something dumb like that again.

Here is the orange 1973 2002 I bought a few years ago. With this car I corrected my poor color choice of my first 2002 and bought one someone else spent their time and energy fixing up. Absolutely crazy fun.

Everyone should own a 2002. What other car can provide this much adventure and offer so many ways to gain experience? Where experience is “the disaster that didn’t kill you.”

Tags: BMW 2002, humility, Intellectual curiosity, meaningful failure, resiliency

January 7, 2025 at 8:10 am |

Wow Pete. Brings back some of my learning moments . Thank you for sharing

LikeLike