My Personal “Boys in the Boat”

By Peter Zaballos

I was a sophomore at a small private high school right at the junction of Oakland and Berkeley. An odd place, a two-story warren of cinderblock classrooms, whose courtyard seemed to capture the ambitions and vanities of the students and staff, focusing them, amplifying them. But I did not really fit in as I had carefully avoided ambition of any kind.

But it was through rowing and the influence of my rowing coach that I found the courage to name an ambition and to act on that ambition. More importantly, I learned to name an ambition that was about more than me, it was about a group. That together as a group, we could have the courage to aspire, to risk, and to win.

An arc of self-discovery so similar to the one eloquently told in Daniel James Brown’s novel, “The Boys in the Boat.”

My classmates came from families who had high expectations – about their own lives and the lives of their children. In that respectat least, my parents fit in. Unlike mine, many of the parents were wealthy, well educated, and motivated. They held high aspirations. They were keen observers of status and stature. And were climbers of social ladders. It was that intersection of interests that captivated my parents.

As children of poor immigrant parents, when it came time to prioritize the lives for their own children, my parents focused almost single-mindedly on education. Not the learning part, not what it does on the inside of a person, but what it gained for you on the outside. The assurance of success, the label, the stamp of approval, a permanent, durable barrier separating the difficult and meager experiences they had from the ones they wanted for us.

The society of this school seemed to cleave cleanly. It was a world where there walked those classmates who knew what they were capable of and had a sense of purpose that was derived from this knowing. And there were the others, like me, struggling for identity and self-substance. Where the word “uncertain” all too frequently could be used to describe my actions and thoughts. A lack of comfort in my own skin.

What could be said for the students could also be said for the school itself. An ambitious emerging institution, whose headmaster’s self-conscious quest for legacy and status could be seen and felt for what it was. Like its students, the school was in its formative years, manifesting assurance and purpose in some areas, tentative uncertainty in others.

There were fewer than 150 of us altogether. A pecking order was established first and foremost by academic prowess, with a similar structure and sorting extended to sports, clubs, and socializing. Wherever you turned there was classification, evaluation, stack ranking.

I had no idea how I got accepted into this place. For as long as I could remember I put the very least amount of myself into school. It wasn’t so much the time, it wasn’t even the effort. It was more basic than that. I methodically and subtly perfected the requisite motions and appearance of participating in an education, while also perfecting the ability to fail, miserably — making a bargain with myself that the freedom of this choice was worth what the price I paid in humiliation in the classroom and at home.

Deep down, if I had had the courage to look closely at myself, I would have seen I lacked the confidence to name ambitions in general, with schoolwork just being the place where I confronted this most visibly.

Yet there did exist a refuge in all of this; sports offered a way to hide in plain sight. The hours spent on a field with others, the hours spent on my own, training, running, riding my bike to get in shape, were hours I was away from the constraining expectations and operations of my education.

It was how I could create a sense of belonging to the school. Soccer in the fall, baseball in the spring. Bookends. Never the star, but always a player.

So, when the headmaster informed us at a daily assembly that the school would be starting a crew team, I was immediately interested. It turned out the father of one of the students had rowed and encouraged the headmaster to start a team. The father even produced a coach, Daig O’Connell, a recent graduate of UC Berkeley and a former member of its varsity team. Anyone interested in joining could come to a meeting after school that day.

Who else would sign up for this? The room filled with a few people, people like me, at the margins of the academic and social strata. The folks who were athletically inclined, but who played in the shadows of the more talented and more ambitious.

We were like a human equivalent of the “Land of Misfit Toys.”

I think Daig couldn’t quite get comfortable with his own experience with crew and the context of our school. Jeez, he’d rowed varsity at Cal, won loads of races, championships, everything. And at Cal there was nothing glamorous about crew; it was serious, hard work.

Daig introduced the term “candy ass” into our lexicon, a term for someone who liked the benefits of hard work but who was unwilling or unable to produce it. At the time we laughed at the mental image and mocking nature of this insult. But it wasn’t until months after he left that it dawned on us he was really speaking about us. We didn’t really work hard. We weren’t serious. And for all Daig’s experience, he just wasn’t a leader.

So while we raced once, it was a slap-dash excuse of a performance; most certainly we could never have been accused of being fluid or graceful. And it came as no surprise that Daig quit at the end of that first season.

But we’d formed some sort of connective tissue within ourselves to one another. We’d found a refuge, an identity of our own creation.

The headmaster? He was hooked. Crew team + private school = exclusive image buff. That seemed to be comfortable math for him.

So he sought out another coach, and soon we were told we had a new one named Giancarlo Trevisan. Giancarlo had an even more impressive pedigree than Daig. He’d been a member of the Italian national crew team and a member of their Olympic team too. Those latter credentials must have been the icing on the cake to bring him on.

There he stood, in pressed slacks, lace-up leather shoes, a neat collared shirt, and one of those light khaki jackets that were so popular in the sixties when he was rowing but looked so awkward and odd in this era. Giancarlo seemed serious, but in this room it was hard to tell if he was serious about his sport or just uncomfortable in these academic surroundings. Maybe it was that he was simply aware of where he found comfort, and that it wasn’t here, indoors.

He was tall and thin, and had the chiseled, dark features we all associated with the stereotypical Italian. His nose seemed to cleave his face in profile; it pointed the way to his smile, or his scowl, both of which began in his eyes.

It was at the first practice the following week, when we stepped into that boathouse, that we realized this was a world wholly different from the one we’d experienced the year before with Daig. Giancarlo was all business, all discipline; matters about rowing, and effort, and expectations were not negotiable. Giancarlo was a leader.

Miles (who later rowed Varsity Heavyweight at Cal), me, Betsy, Humphrey, John and Giancarlo front and center.

We’d carry the shell to the dock, hoist it over our heads, swing it around and place it in the water. No joking, no horseplay. He’d be there, in his launch, watching and waiting. That khaki jacket, those pressed slacks, but with his leather lace-ups replaced with Converse All Stars. And we’d slowly paddle off to begin a workout. He would idle alongside, his face, his demeanor narrowly focusing on the process of learning not so much about how to row, but how to make use of yourself deliberately, openly.

At the “catch” the oar is quickly flipped ninety degrees by the inner hand (the one closest to the oar blade) and dipped into the water. Just as quickly the legs are driven down, with arms acting as a tether, pulling the oar through the water until it’s just about to hit the stomach. Quickly the oar is pushed down while the inner hand again flips the oar 90 degrees, turning the blade horizontal, and you push it away, slide forward, and start the stroke all over again. Hundreds, thousands of times at each practice.

There begins the suffering. Blisters develop on palms and fingers. Butts become sore and numb from sliding up and back on the seat — and I mean that literally, how a part of your body can be both incredibly sore, while also being numb. That inner hand’s forearm becomes leaden from flipping from horizontal to vertical, vertical to horizontal with every stroke. Every time someone’s oar scrapes the water on the backstroke just as it’s being flipped vertical, water gets scooped into the air, hitting whoever is behind in the face with a cold, greenish slap.

Rowing is a complicated sport. The shell is long and thin, with triangular metal “riggers” jutting out at alternating sides, where the oar is locked into place and pivots. One is perched on a seat that slides on rails with feet laced into footrests. Completing a stroke entails pushing the oar forward, blade parallel with the water as it pivots in the oar-lock, body sliding forward until the chest is flat against thighs, with arms extended out to the side the oar is anchored to.

Rest comes in only two sizes: everyone or no one. So caring for yourself, your needs can only be done in motion, in concert, with the rest of the boat. It was this juncture where Giancarlo focused our attention: we were individuals together. It was there that we could see and feel the bright line connecting his passions to his ambitions, his experience to his expectations, his anger to his humor.

On one particularly miserable afternoon early in the season, cold and gray, a light drizzle had succeeded in soaking us just enough so those backstroke splashes felt personal, meant to harm. We were well into the day’s workout, wet and weary, when Giancarlo directed us to turn around, and row another 4,000 meters. And to alternate the tempo between ¾ and full power. Grueling and painful on a good day, but today it just seemed tortuous.

Then John, who rowed the two-seat, said what we were all thinking. “No, I’m not going to do that, I want to go in.” The reaction this provoked in Giancarlo was unambiguous and instantaneous. He was furious and turned his launch around, tilting it over in the turn almost on its side. The rage on Giancarlo’s face was purple and ugly.

In that small launch, with arms and legs flailing, he seemed to be desperately trying to reach across the water and grab John, making the launch rock with each convulsion. “What did you say? You’re going to turn that boat around, now!” He barked these statements in his heavily accented English. He was offended as much by the insubordination of John’s action as he was by the broken commitment to the group, how John had unraveled the group’s integrity. John wanted to go in, because he was tired. But no one could go anywhere by themselves.

Newton’s Third Law saved John: the motion of Giancarlo’s arms towards the shell sent the launch further away from us, which sent Giancarlo into an even greater rage. And made it even harder for him to find his words, because he had to divert his energy and concentration to the rocking launch.

We heard John’s laughter next. It broke the moment. Giancarlo stopped moving, his breathing loud and labored, and then he too broke into a smile, and laughed. And we sat there, letting our relief fill the space where tension and anger had previously been. Giancarlo spoke first. “So, are you ready now?” That was his compromise. The same instruction, but phrased as a question. It called John’s bluff while letting him save face.

We picked up where we had left off, but this time John, without saying a word, helped turn the boat around, and out we went for that next 4,000 meters. Each of us made a little wiser, a little more connected, a little more trusting in each other, and in Giancarlo.

In the boat my skin felt just a little bit more close-fitting. My uncomfortable self worked so very comfortably in this crew team. Removed, away from the school but still part of it. Away, but belonging at the same time. And no place to hide. From myself, from my team-mates, and especially from Giancarlo.

* * * * *

I lived about 25 miles south of my school, in a town not far from where Giancarlo lived. Practices happened in downtown Oakland at Lake Merritt in the late afternoon, and the school would give us rides there, but we needed to make our way home on our own. When practice was over Giancarlo would give me a ride home in his VW bug because my house was on his way home. We’d talk rowing, and life, all the way home. I don’t remember a lot of the specifics, I just remember the relaxed and open tone.

Those drives home, he seemed to know what questions to ask to get a sense of my landscape within, he seemed to perceive that the path I took to become what I was in that boat was neither direct nor easy. Perhaps this is what great coaches do. He saw that little piece that shone through in spite of my best defense. That person I really was and would become.

Over this first season we spent hours and hours together on and off the water, him driving alongside us in the powerboat, shouting instructions in his heavily accented English. I think I saw and experienced every emotion that I was capable of manifesting. Frustration and joy, calm and anger, impatience and flexibility.

I just kept rowing, and he kept teaching. I’d never had to make a choice about a goal and face the possibility of failure, of being out in the open with my ambitions. But this was exactly what Giancarlo was striving to impart, to coax to the surface. For each of us personally, for us as a team.

Other people — our parents, our teachers — had provided much of the basic outlines of our lives. This crew team was different. It was a choice, and there was no place to hide. We’d chosen to grasp the link between a goal and disciplined, hard work. We had to say to ourselves, “I will do this, I want this,” and be witness to that commitment.

We began to understand courage, to take those first glances within and see who and what was there.

With enough practice, technique, skill, and strength, a crew team moves the boat together, not like a marching band, standing next to each other and coordinating movements. But together as if each member was born at the same moment and shares some deep genetic connection. It’s called “swing,” and it’s about becoming able to communicate without speaking, thinking the same thoughts at the same instant, to move and think together as one. And when you achieve swing, this incredibly hard work we are all putting in somehow becomes almost effortless.

It’s swing that enables each member to pay attention to energy levels, reserves and motion within the boat without needing a single word being spoken.

Hands away together, at the same height and speed. Seats forward together, in unison, oars in the water, at the same time and depth, legs driven down with the same transmission of power. Completely effortless, but requiring every ounce of energy and concentration each rower can muster.

At one particularly intense and frustrating practice, we were working on our “power series” — a set of 10 or 20 strokes in the middle of a race where the team might need to put some distance on a competitor or catch up to one who is ahead. It’s a series of strokes meant to break the complacency, break the rhythm in a good way with deliberate, powerful changes. And on this day we just weren’t making a crisp shift in tempo and intensity, it was ragged and disjointed.

Giancarlo was getting frustrated. We were not translating his direction into the actions he expected or felt we were capable of. He was struggling to find the words to convey how differently he wanted these strokes to be and feel. Maybe it was the wind carrying his voice away, but we couldn’t understand what he wanted and it just wasn’t working. And we were frustrated too, because we so wanted that effortless feeling, that sense of unison.

A momentary convulsion rippled through the boat, and it had started with one of my teammates, Humphrey, completely breaking our concentration. What was it? It sounded like laughter. I heard Humphrey blurt out, “Did he say ‘put a pickle in the water’?” In an instant we stopped rowing and doubled over in laughter. Giancarlo swung his launch around but, unlike with the outburst months ago from John’s insubordination, this time approached us with a sense of trust. We were stopping for a reason not related to avoiding effort and strain. We were stopping out of a sense of playfulness, confidence, and assurance.

As he got closer Humphrey shouted to him, “Did you say put a pickle in the water?” Giancarlo cut his engine and let out a laugh. “No,” he shouted back. A pause. “I was saying put a big hole in the water — with your stroke.” That accent did us in. We all laughed, together.

Our four, in the Oakland Estuary, trailing whoever we were racing (“pickle in the water” visible in the upper left corner of the photo).

I think it was there, at that moment, that we realized just how much we had committed ourselves, to our ambitions, to Giancarlo, and to each other. We had learned how to speak the same language, and it had nothing to do with accents. It was having a vocabulary that let us speak of our ambitions. As we approached the competition season, it began to weigh on us that all these months of practice would come down to six minutes of racing time. An entire season’s worth of racing amounting to less than an hour on the clock.

In a race, the rowing is done differently than in practice. The countless hours you’ve spent on the water going back and forth and back and forth are replaced with a sharply defined standoff: you, your competitors, a 2,000-meter straight line, a start and a finish.

Just beginning to move at the start is different. In practice, you just start. No drama, no tension. In a race the start is almost overwhelmingly defined by drama and tension. The rudder is held by someone to keep it in line with the rest of the competitors. Everyone is crouched, seats slid forward, arms and oar extended, so that when the command to start the race is given, the first action is to aggressively apply power to your oar, to move off the line and into the course as quickly as possible.

After the completion of that first stroke, the seat slides forward only part way – to speed the next — and down it goes again. The next time it slides forward a little more, and then again, and within five strokes each rower is taking the full length of the slide, and making long and fast fluid motions. It feels like the slow uncoiling of a tightly wound spring, and it’s a struggle for the team to settle into the more sustainable rhythm needed for the rest of the race. With the start complete, the coxswain takes command, keeping track of where the boat is relative to competitors, getting a sense for the energy and timing of the group and each rower.

Anyone who feels the boat losing ground to a competitor can’t do much on their own to affect that. They need to somehow convey urgency and aggression to each other without any one of them becoming the person who disrupts the progress by going too soon, or pushing or pulling too hard or too fast. They rely on the coxswain’s commands and that unspoken communication among the rowers to understand who has reserves and who doesn’t.

The coxswain’s primary job is to be the jockey of the boat — to understand the race strategy, and adjust the tactics to confront how the race is unfolding — to understand the state of the crew, to read the rower’s abilities, reserves, and confidence. To motivate and direct. The cox also steers the boat, holding a rope in each hand, which trails back to the tiller at the stern of the shell. The rope threads through wooden dowels, which act as grips, and also serve the same purpose as drums did on roman galleys. Those wooden dowels are slapped against the side of the boat (the gunwales) and produce a loud “crack” that is felt as much as it is heard by the rowers. To keep time, to signal urgency.

The coxswain’s more nuanced, more intimate, more fundamentally critical role is communicating where the boat is relative to the competitor.

Competitive progress and results in a race are spoken of using a special lexicon: “seats” (how many seats – places in the boat – a boat is ahead or behind the others), “open water” (that there is a gap between the leader and the next boat), and best of all “lengths”, (how many lengths of a boat separate the leader from the next boat).

We had no idea how good we were, or more importantly, could be. No real first-hand knowledge of how we stacked up against other crews; the prior season had told us so little. If anything it informed us of desire, but what was murky was not knowing if what we desired was achievable. Candy asses or worthy competitors? We didn’t know.

Until our first race.

This is a sport where uniformity is considered a requirement — same height means same stroke length, making it easier for everyone to move together. Same weight/build means more uniform stroke power, making headway more consistent and smooth. But we were a dog’s breakfast of athletes. We ranged in size from 5’ 8’’ (me) to 6’ 3” (Humphrey), more than one of us stocky and muscular, one thin as a string bean.

Like the flight of a bumblebee, where the laws of physics say it shouldn’t be able to fly, the sensibilities and experience of the rowing community said we’d make a poor crew team. We had joined a league with 30 years of history, rowing against schools that had worked to create reputations, had legacies to care about and care for. They were older schools than ours, schools that had earned the elite credentials our school was so actively striving to emulate, or surpass.

A first-time crew coming from this yet-to-be established school, its role in the local education landscape still forming, and with a coach who spoke with an Italian accent — well, whatever reputation preceded us inspired little in the way of fear or respect.

So that first race meant a lot to all of us. When we arrived, the other teams couldn’t believe their eyes when we got out of our cars and walked up to the dock with Giancarlo. Redwood High was the reigning champion, and the first thing their coach said to Giancarlo was “Where’s your varsity?” Not only unwelcoming, but just plain rude. Giancarlo explained, in his accent, that we were in fact the varsity.

It was the nervous look we got from him that told us what we needed to know. Nervous because he wanted to get us on the water, in his and our element.

We got in our seats, tightened the laces on our footrests, put our oars in the oarlocks, closed the cages, and pushed off the dock. We paddled out into the open water and waited for Giancarlo to pull alongside in his motorboat. The warm up was focused, nervous, and silent. Fifteen, maybe twenty minutes of practicing starts and making sure we could transition to a steady tempo for the longer middle section of the race.

“You know what to do. Fast off the start, and then settle down, find your rhythm,” he said as he turned the steering wheel and peeled deliberately away from us. Just as he was about to leave earshot, he added, “Put a pickle in the water,” and punctuated his joke with a broad grin. He was nervous, but not too nervous to be himself.

He’d watch us from his launch, alongside the racers, as we made our way up the course. Out of earshot, out of sight, and out of mind.

We headed to the start line, a series of four small platforms anchored in the water, each boat pulled up to a platform. We backed up to ours, and a race official leaned over and took hold of the boat’s rudder.

Each of us had his seat drawn forward, oar extended, blade in the water, tensed and ready to drive his legs down for that first stroke. We were all waiting to hear the official say “Etes-vous prêt?” (are you ready?) and then the pause before he says “Partez” (go).

Coiled, tense. But the official said “Boat 1 bow-seat take a quarter stroke” to point the boat. A flush of activity in the boat, and we coil again. More silence.

Again it’s the official calling out “Boat 3 two-seat take a quarter stroke.”

More silence. More agony. But then we heard it, “Etes-vous pret?” and a rush of adrenaline hit my bloodstream like a fire hydrant knocked over in a car chase, and the knot in my stomach hurting, burning. Then we heard “Partez.”

The noise was deafening. Seats sliding, oars snapping back against oarlocks, breathing, water splashing. Each rower struggling to keep a clear sense for how the weight was shifting with each stroke, how quickly seats were sliding forward, how much strength got put into the leg drive, into each sweep of the oar.

Those first ten strokes were violent indeed, each rower close to panic, struggling simply to keep up.

As we transitioned from the start sequence to the more deliberate tempo of the race, we also began to let go of individual fears to secure a tighter grip onto collective fears, our collective self.

We were now 50 yards into the 2,000-yard race.

As we found our rhythm, we began to get a sense for what needed to be done. It was subtle, but in these frantic moments, this calm place emerged. We could feel our advantage before we could see its manifestation in our position on the water.

The boat seemed to lift little by little out of the water. We could feel the effort of each stroke seem to diminish the more we moved together. But none dared look to the left or the right, to see where we were against our competitors. Finally someone shouted, “Where are we?”

Our coxswain Betsy shouted back, “We’ve got two seats on Bishop O’Dowd, down a half a length on Redwood. Open water on Berkeley.”

What? Redwood HIgh is the reigning champion, and we were only down a half length. And Berkeley High? They had 2,000 students to choose from. The news hit us like bricks, but bricks from behind, roughly propelling us forward.

Now we could hear the other coxswains, shouting similar updates to their teams. Frantic, loud.

Pickles in the water. We focused on rhythm and channeled our energy, our confidence, to our oars.

“Twenty power strokes, on my mark,” shouted Betsy. We leaned into ourselves, our reserves, but not in a desperate way, in a calm and comfortable way.

At the end of our twenty Betsy delivered the news. “We’ve got open water on Bishop, pulling even on Redwood, 1,000 yards to go,” she shouted. We felt good.

We heard Redwood’s cox call for twenty. “Twenty more, now!” came the response. And there was no desperation or panic in her voice, because she could see how nervous the other team was, she could see the upper hand coming our way.

More pickles in the water: large, comfortable, deliberate, well sized.

Five hundred yards to go and we heard, “We’ve got two seats on Redwood!” She’d stopped telling us about the other teams, they were behind us, and no longer relevant. Instead of calling for power strokes, she just had us pick up the pace in general. Slapping the wooden tiller handles on the gunwales of the boats, making that slap/crack sound we could hear and feel.

We began rowing away from them. The crack of Betsy’s tiller handles was faster than the crack we heard from Redwood. And Redwood could hear this too. And she just kept at it. We no longer had the breath or the energy to ask where we were, and she wasn’t saying. We were more worried about how long we could hold on to this pace than knowing our exact position.

“Twenty more strokes to the finish, give me twenty power strokes!” And that was all we needed. Twenty brutal, grueling strokes, arms, legs, shoulders, lungs — everything on fire.

We crossed the finish line, not sure of anything. Betsy screamed, “We won, we won, we won!” as we slumped over our oars, chests heaving, but quickly leaving that behind to start celebrating. Splashing each other till we were soaking wet with fetid lake water. Screaming with delight and pride.

We looked over at the Redwood team, and the dejection and defeat on their faces was etched in angry acid. We weren’t supposed to win, or even come close.

There was Giancarlo, pulling up alongside of us, a bursting, barely contained smile. And for a moment, we were all there together, unsure of what all this meant. And we lingered, just a bit. In this place of comfort, certainty, trust. Knowing we’d be rowing back to the dock differently than we had rowed out from it.

It was hard to contain the excitement, harder still when we saw the anger, the dejection, frankly, the embarrassment of the other teams. This wasn’t supposed to happen. The boat was up and out of the water in a flash, cleaned and put away even quicker. Giancarlo exchanged pleasantries with Redwood’s coach, but it appeared nothing pleasant was taking place between them.

For the rest of the season we continued to line up at starts with that knot in our stomachs and Giancarlo’s sparse but playful sendoffs. With the same violent conversion of power and energy into fluid, efficient motion. And in the process we made a transformation, gaining an understanding of who and what we truly were, and found rare comfort there.

We won, a lot. Went all the way to the league championship. And won that too.

Our eight, on the right outside lane, at the Nationals in Philadelphia. We would finish third.

Along this arc of achievement, we found a place where our fear and our bravery were held comfortably together in our hands. Making silent pacts with our inner voices, speaking words of hope and naming goals. Articulating ambition, feeling its texture, knowing its taste in our mouth, its scent in the air. Most important, gaining an understanding that ambition and humility can and should be close, intimate friends.

It wasn’t about success, it was that we went down a path of our own choosing, guided and driven by acknowledged ambitions.

* * * * *

A little over a year ago my parents mailed me a set of old photos and awards from when I was a kid, and in with these were some photos of my time on the crew team. Pictures of us, taken from a bridge overlooking one of our races, where we’re all little dots in a boat, with oars outstretched, all perfectly parallel. As we had so meticulously been trained to do.

My favorite photo is the one taken just after we had won the league championships. All of us lined up, holding our oars in the air. We’re wearing shirts that said “CPS Varsity Crew,” our inside joke, going back to that first race. With expressions of joy on our faces. Pure joy. Misfit joy. There’s Giancarlo, kneeling in the front. That wide grin visible, and, if you knew where to look and how to read his expressions, a certain sense of pride. For us, and for him.

So there I was on the phone with my friend Miles, a member of that first team, having not spoken to each other in more than twenty years. We each spontaneously, independently remarked that rowing for this man was the first time each of us had ever felt like a success, at anything. That we had ever felt valued, and valuable, for simply who we were, and who we could be.

It was heartbreaking and wonderful to see how he had had the same effect on each of us.

Giancarlo gave us this place where we could take our very first personal risks. He taught us to be deliberate, and to acknowledge and manifest our own ambition, and he gave us the opportunity to learn what it was we had within ourselves.

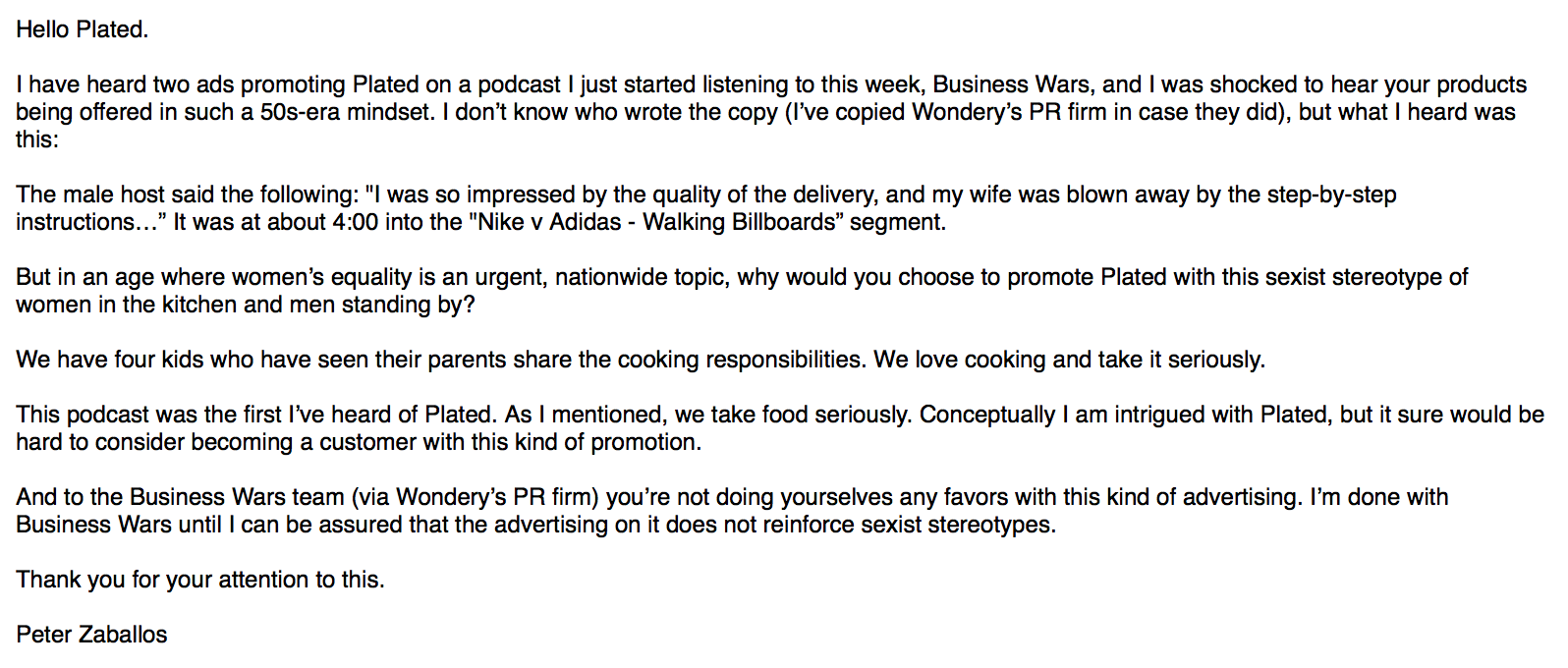

And guess what? I got a machine generated auto-reply from Plated, and nothing from Jon Lindsay Phillips, who is the Executive Director of

And guess what? I got a machine generated auto-reply from Plated, and nothing from Jon Lindsay Phillips, who is the Executive Director of