By Peter Zaballos

TALES FROM THE EARLY-ISH DAYS OF SILICON VALLEY

As the visibly angry man stormed across the break room holding an empty plastic container, I heard him bellow “where’s my damn pâté? Who the hell ate my pâté?”

It was the summer of 1985. I had arrived at this potential LSI Logic customer, Ardent Computer, minutes earlier and was walking with their head of engineering to a conference room to discuss the custom semiconductors they were interested in building.

And that man in search of his pâté? It was none other than Al Michaels: a silicon valley legend who had founded Convergent Technologies, a pioneer of multiprocessor computers.

And his ego — I realized just then — was as large as his reputation.

The head of engineering and I went to the conference room and he described the basic system architecture of the multiprocessor supercomputer and high performance graphics subsystem they wanted to build. They needed custom semiconductors to build the vector processors needed for the graphics subsystem. And there was a sense of urgency here.

You see, Al and his founders had this idea at almost the same time Bill Poduska decided to build a similar supercomputer in Boston. Bill was also a legend in computing, having founded Prime Computer and Apollo Computer. Al and Bill were effectively racing to market, believing the first one to deliver on their promised performance would get the majority of the huge potential.

But that was pretty much 10am on any random Tuesday back in the mid-to-late 80s in silicon valley.

The advent of rapidly customizable semiconductors had unleashed a tidal wave of innovation and startups, all rushing to market. With everyone predicting their product would be the big winner and they’d deliver thousands and thousands of products, even millions, to their customers.

As I mentioned in my earlier blog post, all these companies forecasting huge volume were a blessing and a curse for a semiconductor company. There is a finite amount of capacity in a semiconductor fab, and more than one chip company went under by making poor choices about who to allocate that fixed capacity to. Allocate it to a company that failed in the market and your fab would be empty and your company would have no revenue. Allocate it to a company that succeeded and you’d have that fab running 24/7 shipping crates of completed product.

So while the head of engineering was explaining the nature of the chips they needed built, the sales rep and I had been trained to ask a lot of questions to understand their readiness – where were they on staffing, how complete was the system design, what other dependencies did they have on getting to production, who their investors were.

Our sales reps were bringing multi-million dollar deals to us almost every day. Or rather, “potential” multi-million dollar deals. Part of my job running marketing for Northern California was trying to assess these deals and then sorting out which ones looked the most likely to succeed.

But in reality, it was like I was floating in a fast moving stream and all I was doing was trying not to drown. Too often I would follow the path of a deal rather than affect the path. I was young. I was still finding my voice and experience base. So more often than not I would let momentum dictate the path of a deal

Eventually all deals would flow into a review with all the other marketing managers, the head of sales, the Bill O’Meara (CMO) and at times our Wilf Corrigan (CEO). Frequently my counterpart in sales would make the case for the opportunities in my region – these were their customers, and their literal paychecks on the line.

Ultimately it would fall to Bill and Wilf to make the harder calls. A lot of the less difficult ones my peers and I would work through with Brian Connors and Perry Constantine who headed up sales.

But when I look at my role honestly, I did not do a lot of the advocating, and instead worked furiously to help support the path the deals were already flowing in.

Just as Al Michaels and Bill Poduska were competing to get to market first, I was competing with my colleague, Rick Rasmussen who was responsible for product marketing for the east coast at LSI. Stellar Computer was his potential customer. And we both were likely to need the same allocation of fab capacity.

One of the many reasons I loved the culture at LSI Logic was that we were fierce competitors – in the market. But inside the company there was none of that fierce competitiveness across departments or within departments. We all knew what we were trying to do, and it was to create a blockbuster category and the company that dominated it.

So while Rick and I were competing fiercely for this fab capacity, there was zero animosity between us. In fact, Rick and I were good friends, Rick was the guy I worked with at Fairchild who got recruited to LSI Logic, and it was Rick who recommended they bring me over from Fairchild. [Rick and I would work together at C-Cube Microsystems later in the the 1990s]

But make no mistake, we each knew fab capacity would be tight and we wanted our respective customer to be first in line.

Once I had enough information, I put together a proposed set of pricing for the chips Ardent needed. Our proposals had two components

- The fee to produce the prototypes. This included time in our design center, support from our applications engineers to help with any design issues, the time to run the simulations on our IBM mainframe, the cost of developing the metalization layer mask set for production, and finally, a small wafer set run through production.

- The per-unit price of the completed chips in volume production. We would ask the prospective customer what their forecasted volume ranges would be – and these typically spanned 2-3 years, and then price the chips accordingly.

We pioneered the category of these custom semiconductors and were acknowledged as the market leader, and we had competitors who were nipping at our heels quite aggressively. I had surmised from my conversations with the folks at Ardent that we were the favored supplier.

But LSI had this weird pricing schizophrenia. We tended to come in with a proposal that presumed that as the pioneer and leader, we could charge a premium. And we would generally submit pricing proposals with a pretty hefty premium. The customer would get the proposal and be shocked at how expensive it was. So they would head straight to our competitors and come back with a set of pricing from them that was 50% of what we had proposed.

And what would we do? We’d drop our prices 50% to take the deal. I was in my mid 20s and I just didn’t know any better to question this. Knowing what I know now, this was a stupid self-inflicted wound and the today “me” would have stopped the process and asked a lot of questions about whether we really thought this was a fair price, did this price represent our brand and values? But 26 year-old me was all wrapped up in the headiness of crafting deals like this and working with everyone to bring them home..

I think the origin of our approach to pricing was\ simply hubris. We invented the category. We absolutely knew we were hands-down the best. So I think our corporate ego demanded that we price with a hefty premium. But that same corporate ego was a ruthless competitor and we hated losing business.

It was a stupid move because those customers would react to our suddenly cheaper proposal with a wary eye. “What was that first proposal then? If I had gone with that I would have been paying twice what I am now, and you wouldn’t have told me?”

And that’s what happened at Ardent. My followup meeting with the head of engineering was awkward. He said that Al Michaels was incensed at how we had dropped the price and had no intention of giving us the order. The head of engineering was super frustrated and upset. He and I had gotten to know each other well and spent a lot of time together. He really didn’t want this order to go to our competitor, but our whole pricing process had created a huge mess for him.

And remember, Ardent was competing with Stellar to get to market first. Changing to the competitor chip supplier was going to cost Ardent time. And it was going to make the life of this head of engineering miserable.

He and I both wanted this deal to go to LSI. So I asked if it would help if Bill O’Meara came over and met with Al Michaels. At a minimum this would let Al tell Bill exactly what he thought of our pricing practices. And maybe it would help salvage the deal.

So the meeting got set. I drove over there with Bill and our sales rep along with the rep’s manager. We went into Ardent’s board room and got as settled as we could given the awkwardness of the circumstances. The Ardent team trickled in. About ten minutes after the meeting was supposed to start, Al Michaels came in.

I can’t remember who spoke first, but the head of engineering and I each took turns explaining how hard we all had worked to get this proposal together, how much we respected the other’s time and attention.

Al cut in and said – in the same tone and volume he had expressed astonishment his pâté was missing – “These platitudes are nauseating. We’re here because you’ve wasted our time, which we don’t have a lot of. We worked with you for the past few months on this deal, and you show up with pricing that was so high it was insulting. And then you have the nerve to come back and cut your price in half – only because we got a competitor to give us a reasonable price. How can we possibly trust you? I’ve checked around and we’re not the only company you’ve pulled this on. But the real crime here is our wasted time.”

The room went silent.

Then Bill spoke up.

A bit about Bill. He was one of the four co-founders of LSI Logic and he was not a silicon valley wunderkind. He got started late in his technology career. Bill was a graduate of West Point. The license plate on his car was USMA59. He had learned to lead, he had learned how to earn the respect of his troops. How to motivate and inspire. He was whip-smart and had an equally sharp sense of humor. If you looked up “inspirational leader” in the dictionary, there would be Bill’s photo.

And as you might expect from someone who had been responsible for other people’s lives, he had a disarming ability to connect with people. When you were speaking with Bill it felt like you were the most important person in the world to him right then. Well, because it was true. He was a phenomenal leader.

And as I shared with my Gucci Luggage experience, he had an unshakable sense of ethics. He took full responsibility for his mistakes, and in this case, the mistakes of someone in his organization – me.

He began with “you are right to be outraged and to question whether you can trust us. It was wrong for us to give you such a high priced first proposal and I take full responsibility for how we got here. We were full of ourselves, overconfident and we clearly have to clean up our act. You have my commitment that whether we win this business back or not, we will do the work we need to in order to not repeat this with you or anyone.”

“But I can tell you one reason we priced the way we did is because we also know that we are the best at building custom semiconductors. We invented this category. We have the most reliable technology and process. And we realize your time is precious. What you can count on with us is that once you commit that design to silicon, it will work. And we can scale your production. You can count on that. I’m sorry we broke your trust, but I can assure you we can get you to market faster than anyone.”

Acknowledging our mistake and owning it created an aperture that enabled another twenty minutes of conversation between Bill and Al. The meeting ended and Al said they would have a decision within the next 24 hours.

I believe this meeting was a turning point for LSI Logic. We did examine our proposal process and amended our pricing – not to meet our competitors – to be more competitive with our first proposal.

What Bill didn’t say? What role I had had in the proposal or the role the sales rep and sales manager had had in the proposal. He took complete responsibility. And I believe he did this for a simple reason. If we won this business the salesperson and I were going to have to show up at Ardent frequently. He preserved our relationships.

And while the semiconductor project moved forward, Ardent’s overall product development struggled for reasons not related to our semiconductors. They battled getting the cost of the system down, and as a reset their system design ran into some serious delays.

It turns out so did Stellar’s. In their race to market both companies ran into similar system design challenges. And they were burning cash at a furious rate.

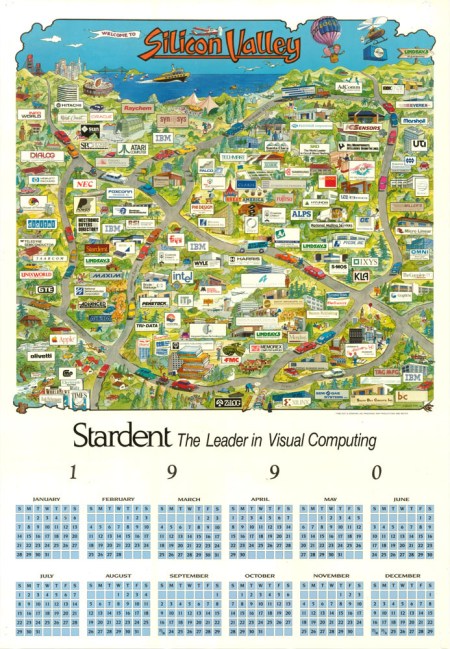

The companies combined forces and changed their name to Stardent (a horribly clunky name, but one that could be logically explained). And they, like so many other promising startups went out of business in the 1990s, a victim of being too expensive for the performance they delivered.

I learned a lot from this experience. I learned about leadership and personal relationships that would eventually show up when I was an executive.

Bill O’Meara’s owning up to when he or the company was wrong, owning when he screwed up made a deep impression on me. In a lot of respects he passed along to me his definition of “ accountability” he learned as an Army commander – something that I would never personally know. And as important he imprinted on me his ability to accept personal responsibility for a mistake someone in his organization might have made.

More than once as an executive I have had to say “I screwed up” or “I made a mistake” – whether I personally made the mistake or someone in my organization did. As the leader of that organization it doesn’t matter who made the mistake. Ultimately the mistake is mine.

Years and years after hearing “Where’s my damn pâté” the Ardent fiasco informed my behavior when I was CMO of SPS Commerce. One of the super, super talented product managers on my team was about to introduce a fundamental redesign of our core product – a product tied to 80% of our revenue. The stakes were incredibly high. We were a public company and this product launch had to go very smoothly.

The week of the launch, I pulled the product manager aside and told her “This is your product, you’ve put 18 months into leading and orchestrating the redesign and have done a fabulous job. This week as you’re on stage launching this to the company and all our customers, I’m not going be anywhere visible. This is your product and your time in the limelight. But if anything happens, if anything goes wrong for whatever reason, I will be out front and be very visible. So go out there and soak it all in, and do that knowing I have your back the whole time.”

And because she was so damn good at her job, that whole week no one saw me.